The Complete Guide to Beef Primal Cuts

When I was twelve years old, my grandfather Sal stood me in front of a hanging beef carcass in the walk-in cooler of his Brooklyn butcher shop and said, "Frankie, before you touch a knife, you gotta know the animal." That lesson stuck with me through 40 years behind the counter. Understanding where a cut comes from — what that muscle did during the animal's life — tells you almost everything you need to know about how to cook it.

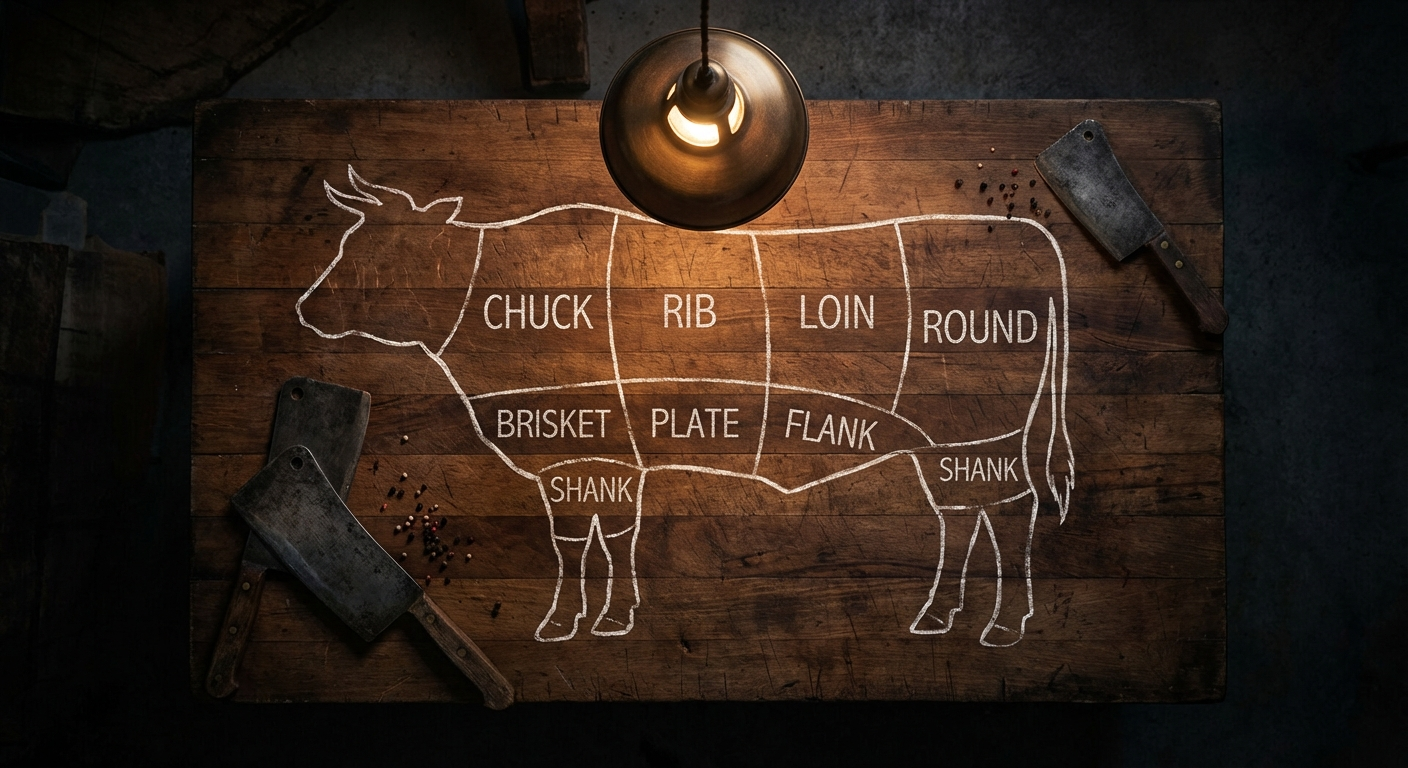

A beef carcass is divided into eight primal cuts. These are the first major sections separated during processing, and everything you see in the butcher case comes from one of them. Think of primals as the chapters of a book — once you know the chapter, you understand the story.

The Forequarter (Front Half)

The forequarter includes everything from the front of the steer: the shoulder, rib, chest, and belly. These muscles tend to be harder working (the animal supports 60% of its weight up front), which means more connective tissue and more flavor — but often more toughness too.

1. Chuck (The Shoulder)

The chuck is the shoulder and neck of the steer, accounting for roughly 26% of the carcass weight. It's the single largest primal, and for decades it was considered a "lesser" cut — ground beef and pot roast territory. That reputation has changed dramatically.

The chuck contains over a dozen individual muscles, each with different characteristics. When you buy a "chuck roast" at the grocery store, you're getting a cross-section through several of these muscles at once. But when a skilled butcher seam cuts the chuck — separating muscles along their natural boundaries — you unlock cuts that rival the premium primals.

The flat iron steak, for example, comes from the top blade muscle in the chuck. University researchers identified it as the second most tender muscle in the entire carcass. The Denver steak, from the serratus ventralis, has rich marbling and a price point well below a ribeye. Chuck eye steaks, cut from the center of the chuck roll, are so similar to ribeyes that many people can't tell the difference in a blind tasting.

Best cooking methods: Braising for roasts and tough cuts, grilling for flat iron and Denver steaks, smoking for chuck roast ("poor man's brisket").

Price range: $5–$12/lb for Choice, depending on the specific cut.

2. Rib (The Money Cut)

The rib primal spans ribs 6 through 12 along the upper back, just behind the chuck. This is where the real money is in the beef business — and where the eating gets extraordinary.

What makes the rib special is the combination of tenderness and marbling. These muscles do relatively little work compared to the chuck or round, so they stay naturally tender. Meanwhile, the intramuscular fat deposits here are among the heaviest in the carcass, especially in higher-grade cattle.

The ribeye steak is the crown jewel — a cross-section of the longissimus dorsi, spinalis dorsi (the "cap"), and complexus muscles. The spinalis dorsi (ribeye cap) is, in my professional opinion, the single best-tasting cut of beef that exists. Some specialty shops will peel it off and sell it separately. If you ever see it, buy it. Don't even look at the price.

The standing rib roast — prime rib — is the same muscles left intact as a multi-rib roast. A 3-bone standing rib roast, seasoned simply with salt and pepper and roasted to medium-rare, is one of the great culinary achievements you can pull off at home.

The difference between USDA Prime and Choice is most visible and impactful in the rib primal. Prime ribeyes look like they've been marbled by a painter — white flecks throughout. Select ribeyes can look almost entirely lean. The eating difference is enormous.

Key cuts: Ribeye steak, tomahawk, cowboy steak, prime rib, back ribs.

Price range: $16–$45/lb for Choice to Prime.

3. Brisket (The BBQ King)

The brisket comes from the chest — the pectoral muscles that support 60% of the animal's weight. A whole packer brisket has two muscles (the flat and the point), separated by a fat layer, weighing 12 to 20 pounds.

Raw brisket is one of the toughest cuts you'll encounter. It's loaded with collagen and connective tissue. But apply low heat and patience — 225–275°F for 12–18 hours — and the collagen converts to gelatin. The result is one of the most tender, flavorful preparations in all of American cuisine.

When buying brisket for smoking, always buy the full packer, not a trimmed flat. Grade matters — USDA Prime briskets have significantly more intramuscular fat, which means more moisture and flavor through the long cook. Upper Choice (Certified Angus Beef) is the minimum I'd recommend.

The "flex test": When picking up a packer brisket, drape it over your hand. A well-marbled brisket will bend and flex; a lean one stays rigid. Go with the floppy one.

Price range: $4–$9/lb for Choice, $7–$14/lb for Prime.

4. Plate (The Hidden Gems)

The plate (or short plate) sits on the underside of the steer, below the rib. It's a relatively small primal, but it produces some of my absolute favorite cuts.

Short ribs are the star — whether English-cut (bones separated) or flanken-style (cut across the bones into thin strips). Plate short ribs, specifically, are the massive, dinosaur-bone-looking ribs that have become a BBQ restaurant staple. They're incredibly meaty and, when smoked properly, produce some of the most spectacularly tender beef you'll ever eat.

The outside skirt steak is here too — the diaphragm muscle. It's the real skirt steak (as opposed to the inside skirt, which comes from the flank area and is thinner, tougher, and less flavorful). Most outside skirt gets exported to Japan or goes to restaurants, which is why you rarely see it at retail. If your butcher has it, don't hesitate.

And then there's the hanger steak — one per animal, about 1–1.5 lbs, hanging from the diaphragm. It's called the "butcher's steak" because butchers used to keep it for themselves. Intensely beefy, almost liver-like in its depth of flavor. Cook it hot, cook it fast, don't go past medium-rare.

Price range: $8–$15/lb for Choice, depending on cut.

5. Shank (The Braiser's Best Friend)

The shank is the lower front leg. These are the hardest-working muscles on the animal — and they're loaded with collagen, connective tissue, and bone marrow.

You cannot cook shank quickly. Don't try. But braise it for 3 hours and you'll understand why osso buco is one of the great dishes of Italian cuisine. Cross-cut shanks, with that beautiful marrow bone in the center, transform into something magical with time and liquid.

At $4–$7/lb, shank remains one of the best values in the case. The bone marrow alone is worth the price of admission.

The Hindquarter (Back Half)

The hindquarter includes the back and legs of the steer. This is where you find the most tender muscles (the loin) and the leanest (the round).

6. Loin (The Tenderest Cuts)

The loin runs along the upper back behind the rib. It's divided into the short loin (where you find strip steaks, T-bones, and porterhouses) and the sirloin (top sirloin, tri-tip).

The short loin is home to two of the most popular steaks in America: the New York strip (from the longissimus dorsi) and the tenderloin/filet mignon (from the psoas major). The T-bone and porterhouse steaks include both, separated by a T-shaped vertebral bone. The difference between a T-bone and a porterhouse is simply the size of the tenderloin section — the USDA requires a porterhouse to have at least 1.25 inches of tenderloin measured from the bone.

The tenderloin is the most tender muscle because it does virtually no work — it's an internal muscle along the spine. It's also the leanest of the premium cuts, which is why filet mignon is often wrapped in bacon or served with rich sauces. On its own, it's tender but not particularly flavorful compared to a ribeye.

A whole tenderloin (called a PSMO — peeled, side muscle on) is one of the best value purchases for home cooks. Buy the whole muscle, trim and cut it yourself, and you'll pay $20–$35/lb instead of $35–$50/lb for pre-cut filets.

Key cuts: NY strip, filet mignon, T-bone, porterhouse, top sirloin, tri-tip.

Price range: $12–$50/lb depending on cut and grade.

7. Round (The Lean Machine)

The round is the rear leg — roughly 22% of the carcass. It's large, lean, and economical. It's not glamorous, but it has its place.

Because these are locomotion muscles, they're low in fat and can be tough. Top round makes excellent roast beef when cooked low and slow to medium-rare and sliced paper-thin. Bottom round is a solid braising cut. Eye of round is lean enough to make great jerky and serviceable oven-roasted deli meat.

The key with round cuts is never overcooking them. Without fat to keep things moist, the margin for error is razor-thin. A thermometer is mandatory.

Best uses: Roast beef, jerky, stir-fry (sliced thin), braised pot roast, ground beef (lean component).

Price range: $5–$8/lb for Choice.

8. Flank (The Fajita King)

The flank is a flat, lean muscle from the abdominal area. It has pronounced muscle fibers (visible grain), intense beef flavor, and a versatility that's made it one of the most popular cuts in America.

The absolute, non-negotiable rule with flank steak: slice thin, against the grain. Cut perpendicular to those visible fiber lines. If you cut with the grain, you'll be chewing for days regardless of how perfectly you cooked it. Against the grain, properly, and it's butter.

Flank used to be a $4/lb budget cut. Those days are gone — it now runs $10–$14/lb for Choice. Popularity killed the deal. But the flavor-to-value ratio is still excellent.

Classic uses: Fajitas, carne asada, stir-fry, London broil, stuffed and rolled (braciole).

Putting It All Together

Here's the framework I want you to take away: the harder a muscle works during the animal's life, the more flavor it develops and the more connective tissue it builds. Center-of-the-animal cuts (rib, loin) are tender because those muscles don't do much. Extremity cuts (chuck, round, shank) are tougher but more flavorful because they're constantly working.

Tender cuts → high heat, fast cooking. Grill, sear, roast.

Tough cuts → low heat, slow cooking. Braise, smoke, sous vide.

Match the method to the muscle, and you'll nail it every time. That's the lesson my grandfather taught me in that walk-in cooler, and it hasn't steered me wrong in 40 years.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the 8 primal cuts of beef?

The 8 beef primal cuts are chuck (shoulder), rib, loin, round (rear leg), brisket (chest), plate (belly), flank (lower belly), and shank (lower leg). The forequarter contains chuck, rib, brisket, plate, and shank. The hindquarter contains loin, round, and flank.

Which primal cut is the most tender?

The loin primal produces the most tender cuts, including the tenderloin (filet mignon) and NY strip. The tenderloin is the single most tender muscle because it does virtually no work during the animal's life.

Which primal cut has the most flavor?

The rib and chuck primals are generally considered the most flavorful. The rib combines excellent marbling with moderate tenderness, while the chuck's harder-working muscles develop deep, complex beef flavor.

What is the cheapest primal cut of beef?

The round (rear leg) and shank (lower leg) are typically the most affordable primals, ranging from $4-$8/lb for USDA Choice. These leaner cuts require specific cooking methods but offer excellent value.

More Expert Guides

Understanding USDA Beef Grades: Prime vs Choice vs Select

What do USDA grades actually mean? A veteran butcher cuts through the marketing to explain how beef grading works, what you're paying for, and when it matters most.

14 min readWhat is Wagyu Beef? A Butcher's Honest Guide

Wagyu is the most misused word in the meat industry. Here's what it actually means, how to tell real from fake, and whether it's worth your money.

11 min readHow to Choose the Right Steak Cut for Any Occasion

Not every steak is right for every situation. A veteran butcher matches the perfect cut to your occasion, budget, and cooking method.